Elisa di Liang Kelinci

Lewis Carroll (nukilan novel Petualangan Elisa di Negeri Ajaib)

Terjemahan Eliza Vitri Handayani

Elisa mulai merasa sangat bosan, duduk di samping kakaknya di tepi sungai, hanya beruncang-uncang kaki. Sekali, dua kali, ia mengintip ke dalam buku yang dibacakan kakaknya, tapi tak ada gambar, tak ada balon suara di dalamnya. “Apa asyiknya buku yang tak ada gambarnya?” pikir Elisa, “yang tak ada balon suaranya?”

Jadi, dalam benaknya, ia menimbang apakah kepuasannya merangkai kalung bunga aster bakal sepadan dengan upayanya bangun dan memetik bunga-bunga itu. (Elisa berpikir sekuat tenaga, namun sulit, sebab teriknya matahari membuatnya sangat mengantuk dan berkunang-kunang.) Tiba-tiba, seekor Kelinci Putih dengan mata merah jambu melintas di dekatnya.

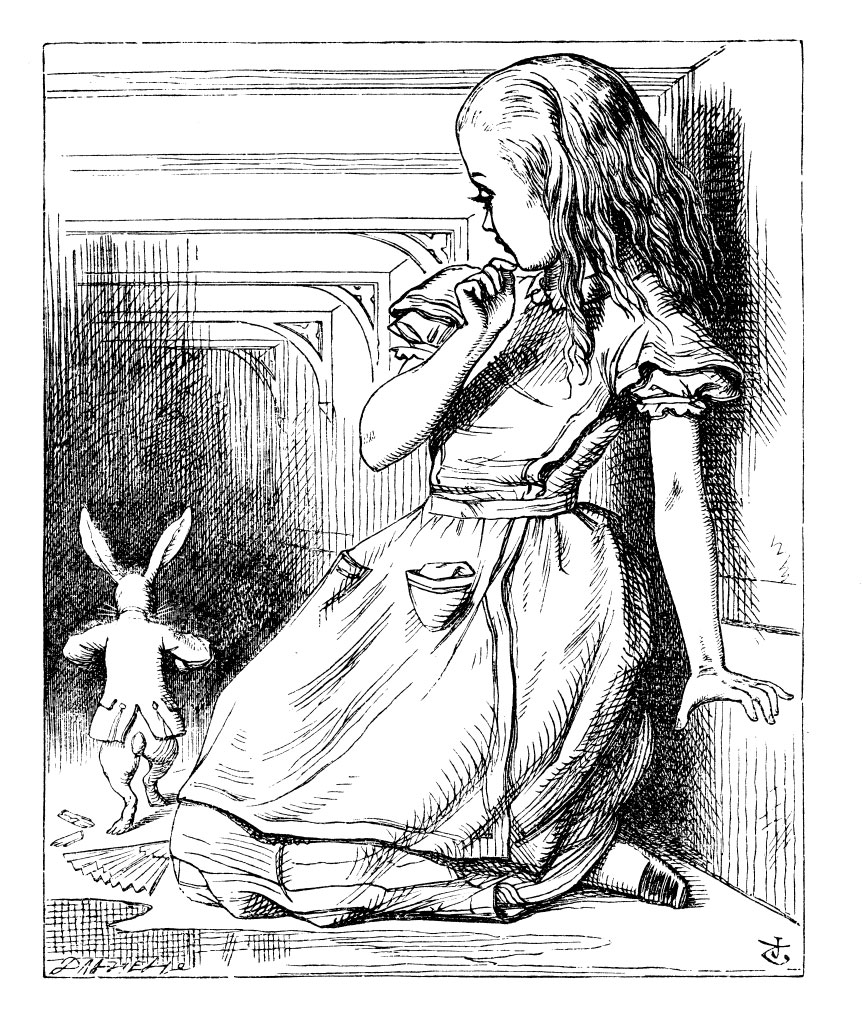

Tak ada yang sungguh-sungguh istimewa dengannya; Elisa pun pikir tidak sungguh-sungguh aneh ketika didengarnya si Kelinci berkata, “Oh tidak! Oh tidak! Aku terlambat!” (Ketika nanti Elisa pikir-pikir lagi, barulah terbersit olehnya betapa aneh semua itu, tapi saat ini semua tampak wajar-wajar saja baginya.) Namun, ketika si Kelinci mengeluarkan arloji dari saku jasnya, melihat jam berapa, lalu lekas berlari lagi, Elisa bangkit berdiri, sebab tiba-tiba sadarlah ia: tak pernah sebelumnya ia lihat kelinci memakai jas atau memiliki arloji di dalam sakunya. Maka, terpecut rasa penasaran, larilah Elisa melintasi padang rumput mengejar si Kelinci, tepat waktu untuk melihatnya melompat ke dalam sebuah liang di bawah semak-semak.

Tanpa buang waktu, Elisa ikut melompat, juga tanpa berpikir bagaimana nanti dia bisa keluar.

Liang kelinci itu memanjang seperti terowongan, lalu tiba-tiba menukik jatuh, tiba-tiba sekali, Elisa sampai tak sempat mengerem, tahu-tahu dia jatuh tegak lurus, seperti dalam sebuah sumur yang dalam sekali.

Entah sumurnya yang sangat dalam, atau dia yang jatuh dengan sangat perlahan, pokoknya Elisa punya banyak waktu untuk melihat-lihat sekitarnya, dan mengira-ngira apa yang akan terjadi kemudian. Pertama, ia coba memandang ke bawah, cari tahu akan mendarat di mana, tapi ujung liang tak kelihatan karena terlalu gelap; lalu, ia memandang ke sisi sumur, dan diperhatikannya banyak lemari dan rak buku di sekelilingnya, di sini dan di sana dilihatnya banyak peta dan lukisan tergantung. Diambilnya sebuah toples dari salah satu rak, 'SELAI JERUK' tertulis di labelnya. Sayangnya, toples itu kosong. Elisa kecewa. Namun, Elisa tak ingin melepaskan toples itu begitu saja, khawatir ia menimpa seseorang di bawah, jadi dikembalikannya ke salah satu lemari yang dilewatinya.

“Wah!” pikir Elisa sendiri. “Setelah jatuh seperti ini, aku takkan takut seandainya jatuh dari tangga. Semua orang bakal anggap aku sangat berani! Aku takkan mengeluh sama sekali, seandainya pun aku jatuh dari atap rumah!” (Kemungkinan besar orang yang jatuh dari atap rumah memang takkan mengeluh.)

Terus, terus jatuh. Apakah takkan pernah berakhir? “Entah sudah berapa kilometer aku jatuh,” kata Elisa keras-keras. “Mestinya aku sudah dekat ke inti bumi. Coba: kalau tidak salah jaraknya enam ribu kilometer—" (Elisa sudah belajar beberapa hal seperti ini di ruang kelas, dan meskipun sekarang bukan waktu yang paling baik untuk memamerkan pengetahuannya, sebab tidak ada yang bisa mendengarnya, tetap saja baik untuk mengingat-ingat pelajaran) “—ya, kira-kira sejauh itu jaraknya—tapi, berapa derajat lintang utara atau selatan, bujur barat atau timur, lokasiku ya?” (Elisa sama sekali tidak tahu apa itu Lintang Utara dan Selatan, Bujur Barat dan Timur, tapi ia senang mengucapkan kata-kata itu.)

Tak lama kemudian ia mulai lagi. “Penasaran, apakah aku akan jatuh terus, menembus bumi? Betapa anehnya jika aku ketemu orang-orang yang berjalan dengan kepala di bawah! Orang-orang Antipati namanya, kalau tidak salah..." (kali ini Elisa senang tak ada yang bisa mendengarnya, sebab ia sama sekali tidak yakin itu namanya) “Tapi aku bakal harus tanya apa nama negara mereka. Permisi, Bu, apa ini Selandia Baru? Atau Australia?” (dan ia coba membungkukkan badan seraya bicara—bayangkan sulitnya membungkuk sambil jatuh! Kau pikir kau sendiri bisa?) “Ibu itu pasti menanggap aku ini tolol sekali, nama negara saja tidak tahu. Ah tidak, aku tak boleh bertanya, siapa tahu bisa kulihat tertulis di tanda jalan.”

Terus, terus jatuh. Tak ada lagi yang bisa ia lakukan, jadi Elisa mulai bicara lagi. “Dinah pasti sangat merindukanku malam ini.” (Dinah itu si meong.) “Semoga saja ada yang ingat memberinya susu saat makan malam. Dinah sayang, andai kau ada di sini bersamaku! Tidak ada tikus di terowongan ini, sayangnya, tapi siapa tahu ada keong, dan keong kan seperti tikus yang punya cangkang. Tapi, apa meong mau makan keong?” Sekarang Elisa mulai mengantuk, dan mulai bergumam sendiri, setengah tertidur: “Meong mau makan keong?” lalu, “Keong mau makan meong?” Tak masalah bagi Elisa bagaimana ia menyusun pertanyaannya, sebab ia toh tak mampu menjawabnya.

Elisa mulai terlelap dan bermimpi berjalan bergandeng tangan dengan Dinah, sambil bertanya: “Dinah, jawab sejujurnya ya, kamu pernah tidak makan keong?” Tiba-tiba: dung! dung! Mendaratlah ia di atas tumpukan jerami dan daun kering. Usai sudah jatuhnya.

Elisa tidak terluka sama sekali, ia justru segera melompat berdiri. Ia mendongak, tapi di atas kepalanya semua gelap, di hadapannya terbentang sebuah gang panjang, dan dilihatnya si Kelinci Putih berlari menyusurinya. Tanpa membuang sedetik pun, Elisa melesat mengejarnya, tepat waktu untuk mendengarnya berkata, seraya ia berbelok di tikungan, “Demi kuping dan kumisku, aku sangat terlambat!” Elisa nyaris menyusul si Kelinci, tapi ketika ia berbelok, si Kelinci sudah raib.

Elisa temukan dirinya di sebuah aula yang panjang dan rendah, diterangi oleh sebaris lampu yang tergantung di langit-langit. Ada banyak pintu di sekeliling aula, tapi semuanya terkunci! Setelah Elisa selesai mengelilingi ruangan, mencoba tiap-tiap pintu, satu demi satu, dengan sedih ia berjalan kembali ke tengah, bingung bagaimana dia bisa keluar dari situ.

Tiba-tiba dilihatnya sebuah meja mungil berkaki tiga, seluruhnya terbuat dari kaca. Tidak ada apa-apa di atasnya, kecuali sebuah kunci emas mungil. Segera saja Elisa pikir, “barangkali kunci salah satu pintu di sini.” Tapi sayang, semua lubang kunci terlalu besar, atau kunci itu yang terlalu kecil, sehingga Elisa tak bisa membuka satupun pintu di sana. Namun, saat ia berkeliling kedua kali, diperhatikannya ada tirai pendek yang tidak ia lihat sebelumnya, dan di balik tirai itu ada sebuah pintu setinggi kira-kira empat puluh senti. Dicobanya membuka pintu itu dengan kunci emas tadi—dan berhasil! Elisa girang sekali.

Dibukanya pintu dan dilihatnya ada terowongan mungil di baliknya, tidak lebih besar daripada liang tikus. Elisa bertiarap dan menerawang, dilihatnya di ujung gang itu taman terindah sedunia. Betapa ia ingin keluar dari aula temaram tempatnya berada dan menelusuri rumpun-rumpun bunga cerah dan kolam-kolam jernih. Tapi bahkan kepalanya saja tak muat melalui pintu!

“Seandainya pun kepalaku muat,” pikir Elisa malang, “apa gunanya tanpa bahuku? Oh, seandainya saja aku bisa dikerutkan seperti teleskop! Kukira pasti bisa, asalkan aku tahu harus mulai dari mana.” Begitu banyak hal luar biasa telah terjadi hari ini, sehingga Elisa mulai berpikir sangat sedikit hal di dunia ini yang sebenarnya mustahil.

Tampaknya tak ada gunanya menunggu di depan pintu mungil itu, jadi ia kembali ke meja kaca tadi, setengah berharap akan menemukan sebuah kunci lain di sana, atau paling tidak sebuah buku yang menjelaskan bagaimana mengerutkan orang seperti teleskop. Kali ini, ditemukannya sebuah botol mungil (“Aku yakin botol ini tadi tidak ada,” kata Elisa) berkalung sebuah label kertas: 'MINUM AKU' tertulis indah dengan huruf-huruf besar.

Boleh saja labelnya bilang 'Minum aku', tapi Elisa kecil yang bijak tidak mau terburu-buru melakukannya. “Biar kulihat dulu," katanya, “siapa tahu ada tanda ‘racun'." Ia sudah pernah baca beberapa cerita tentang anak-anak yang terbakar, atau dimangsa binatang buas, atau tertimpa nasib buruk lainnya, hanya karena mereka tidak ingat beberapa peraturan sederhana yang telah diajarkan kawan-kawan, misalnya: tongkat yang berkilau merah akan membakar kulitmu jika kau memegangnya terlalu lama, dan jika kau mengiris jarimu dalam-dalam dengan pisau, kau akan berdarah; Elisa juga takkan lupa, jika kau minum terlalu banyak dari botol yang bertanda ‘racun’, ia jelas akan berakibat buruk bagi kesehatanmu, cepat atau lambat.

Namun, botol mungil ini tidak bertanda ‘racun’, jadi Elisa mencicipinya. Ternyata rasanya enak juga (tepatnya, seperti campuran pai ceri, saus vanila, nanas, kalkun panggang, karamel, dan roti bakar bermentega), dan tak lama kemudian ia minum habis.

* * * * *

* * * *

* * * * *

“Aneh betul,” kata Elisa, “tubuhku terasa mengerut seperti teleskop.”

Memang begitulah: sekarang Elisa cuma dua puluh lima senti tingginya. Wajahnya berseri-seri membayangkan kini ia akan muat melalui pintu mungil yang menuju taman indah tadi. Sebelum berlari, ia menunggu beberapa menit untuk lihat apakah ia akan terus mengerut—ia cemas juga. “Jangan-jangan,” kata Elisa sendiri, “aku terus-menerus bertambah kecil hingga habis, seperti lilin. Kalau sudah begitu, apa jadinya diriku?” Ia mencoba membayangkan seperti apa rupa api lilin setelah lilin itu habis terbakar, sebab ia tak ingat pernah melihat sesuatu seperti itu.

Setelah beberapa saat, dan tak ada lagi yang terjadi, Elisa memutuskan untuk segera pergi menuju taman tadi—tapi, kasihan betul Elisa, ketika ia sampai, pintu sudah kembali terkunci, dan ia baru ingat kunci emas tadi tertinggal di atas meja. Ketika ia kembali ke meja, ia sadar ia tak cukup tinggi untuk meraihnya. Ia bisa lihat kunci itu melalui kaca, dan dicobanya sekuat tenaga memanjat salah satu kaki meja, tapi terlalu licin. Dan setelah ia kelelahan mencoba dan mencoba lagi, Elisa kecil yang malang duduk di lantai dan menangis.

“Sudah, tak ada gunanya menangis seperti ini!” kata Elisa, agak keras, kepada dirinya sendiri. “Ayo bangun sekarang juga!” Pada umumnya ia mampu beri dirinya nasihat baik (meskipun jarang sekali ia ikuti), dan kadang-kadang ia marahi dirinya dengan garang sekali sampai ia menangis; dan ia ingat pernah sekali ia coba membungkus airmatanya, kala itu ia marahi dirinya sendiri karena curang ketika main croquet lawan dirinya sendiri—anak aneh ini memang senang berpura-pura jadi dua orang. “Tapi tak ada gunanya sekarang berpura-pura jadi dua orang,” pikir Elisa. “Kini aku bahkan terlalu kecil untuk jadi satu orang normal.”

Tak lama kemudian matanya jatuh pada sebuah kotak kaca mungil di kaki meja, dibukanya, dan ditemukannya di dalam sebuah kue kecil dengan taburan kismis mengeja 'MAKAN AKU'.

“Baiklah, akan kumakan,” kata Elisa, “jika aku melar, aku bisa ambil kunci di atas meja; jika aku ciut, aku bisa menyusup melalui kolong pintu—bagaimanapun aku akan bisa ke taman, dan aku tak peduli dengan cara yang mana.”

Digigitnya sebagian, dan mulai bergumam cemas, “Melar atau ciut?” Disentuhnya ubun-ubun supaya bisa merasakan apakah ia jadi tambah besar atau tambah kecil—tapi, ia lumayan terkejut ketika sadar, tingginya tak berubah. Jelas, inilah yang biasanya terjadi ketika kita makan kue, tapi Elisa telanjur terbiasa mengharapkan hal-hal yang luar biasa, sehingga kini sungguh membosankan dan konyol rasanya ketika sesuatu terjadi seperti biasanya.

Maka Elisa pantang menyerah, dan tak sampai semenit kemudian tandaslah kue tadi.

* * * * *

* * * *

* * * * *

“Sungguh aneh sepaling-anehnya!” seru Elisa (ia terkejut menyadari ia lupa menggunakan tata bahasa yang baik). “Sekarang aku melar seperti teleskop terbesar yang pernah ada! Sampai jumpa, kaki!” (ketika ia menunduk, kakinya sendiri nyaris tak terlihat, sebab kepalanya sudah jadi tinggi sekali). “Oh, kasihan kaki kecilku, sekarang siapa yang akan memakaikan sepatu dan kaus kaki untukmu? Yang jelas aku tak bisa. Aku terlalu jauh untuk mengurusmu, kamu berdua mesti bisa mandiri semampu mungkin!” Lalu Elisa pikir, “Tapi aku mesti bersikap baik terhadap mereka, atau jangan-jangan mereka takkan mau berjalan ke arah yang kukehendaki. Hmm, barangkali aku bisa beri mereka sepasang sepatu bot tiap Natal.”

Dan ia mulai merencanakan bagaimana mesti mengirim hadiah itu. “Harus melalui kurir,” pikir Elisa. “Alangkah lucunya, mengirim hadiah untuk kaki sendiri. Dan betapa ganjil labelnya nanti!

Kepada: Kaki Kanan Elisa

Di Atas Karpet,

Di Dekat Perapian

(dengan cinta).

Ya ampun, bicaraku sungguh tiak masuk akal!”

Tiba-tiba saja kepalanya membentur langit-langit, saat ini ia nyaris tiga meter tingginya, dan cepat-cepat disambarnya kunci emas dan bergegas ke pintu taman.

Kasihan Elisa! Sekarang yang bisa ia lakukan hanyalah berbaring di satu sisi dan menerawang ke taman dengan sebelah mata. Kini lebih mustahil lagi baginya untuk melalui pintu mungil itu. Elisa duduk dan mulai menangis lagi.

“Seharusnya kamu malu,” katanya, “kamu kan sudah besar,” (tepat, bukan, untuk situasinya?) “buat apa menangis seperti anak kecil? Berhenti sekarang juga!” Tapi Elisa terus menangis, menumpahkan bergalon-galon airmata, sampai terbentuklah genangan air di sekitarnya, sedalam sepuluh senti dan menutupi separuh permukaan aula.

Setelah beberapa menit ia mendengar langkah-langkah kaki kecil di kejauhan, lekas-lekas ia keringkan matanya supaya bisa melihat siapa yang datang. Ternyata si Kelinci Putih, kini ia berdandan necis, tangan kirinya memegang sepasang sarung tangan putih dan tangan kanannya memegang kipas yang lebar. Derap langkahnya tergesa-gesa, dan ia terus saja berteriak sendiri, “Oh! Nyonya Duchess, Nyonya Duchess! Ia pasti jadi bengis kalau kubiarkan menunggu!”

Elisa yang sudah merasa sangat putus asa siap minta tolong kepada siapa saja, maka ketika si Kelinci melintas di dekatnya, ia berkata dengan suara yang rendah dan malu-malu, “Permisi, Pak—” Si Kelinci terkejut luar biasa, sarung tangan putih dan kipasnya sampai jatuh, lalu ia bergegas melesat ke kegelapan secepat kakinya mampu berpacu.

Elisa memungut sarung tangan dan kipas itu, dan karena kegerahan ia mulai mengipas-ngipas sambil berkata, “Astaga, astaga! Alangkah ajaibnya semua yang terjadi hari ini! Padahal kemarin semua terjadi seperti biasa. Jangan-jangan aku yang berubah kemarin malam? Tunggu sebentar: apakah tadi pagi ketika bangun tidur aku masih sama dengan aku yang sebelumnya? Aku nyaris ingat merasa sedikit berbeda. Tapi andai aku sudah berubah, pertanyaan berikutnya adalah, ‘Siapa aku sekarang?’ Nah, itu dia misteri besarnya!” Dan ia mulai mengingat-ingat semua anak yang dikenalnya, yang seusia dengannya, untuk cari tahu apakah ia sudah berubah jadi salah satu dari mereka.

“Aku yakin aku bukan Aida,” katanya, “sebab rambutnya panjang keriting, dan rambutku sama sekali tidak keriting; aku juga yakin aku bukan Bela, sebab aku banyak tahu tentang banyak hal, dan dia, oh, sangat sedikit hal yang diketahuinya. Lagipula, dia kan dia, dan aku kan aku—ah, sungguh membingungkan semua ini! Coba, apa aku masih tahu segala hal yang dulu kuketahui? Empat kali lima sama dengan dua belas, empat kali enam sama dengan tiga belas, empat kali tujuh sama dengan—aduh, pasti aku salah, sebab aku takkan sampai dua puluh jika terus begitu. Lagipula, tabel kali-kalian tidak berarti apa-apa, ayo kita coba Geografi. London ibukota Paris, Paris ibukota Roma, dan Roma—aduh, salah lagi! Tuh kan, aku pasti sudah berubah jadi Bela! Oke, sekarang aku coba melafalkan puisi Lihatlah si buaya kecil...” Dilipatnya tangannya di pangkuan, seperti sering dilakukannya saat pelajaran menghafal, dan mulai mendeklamasikan puisi tadi. Namun, suaranya terdengar kasar dan asing, dan kata-katanya tidak mengalir seperti biasanya:

“Lihatlah si buaya kecil!

Mengibas ekornya yang bersisik

Dan mencipratkan air sungai Nil

Ke orang-orang yang berisik.

“Betapa riang ia tampil,

Merentangkan kuku dan cakar,

Dan menyambut ikan-ikan mungil

Dengan moncong tersenyum lebar.”

“Aku yakin itu bukan kata-kata sebenarnya!” seru Elisa, sekali lagi matanya tergenang airmata. “Aku pasti sudah berubah jadi Bela, dan aku harus tinggal di rumahnya yang sempit dan beratap runcing, dan aku takkan punya banyak mainan, dan, oh, aku harus belajar semua hal dari awal lagi! Tidak, tekadku sudah bulat, jika aku jadi Bela, aku akan tinggal di ruangan ini! Orang-orang boleh saja menjulurkan kepala mereka ke dalam liang dan memanggil, 'Ayo naik, Sayang!' Aku hanya akan mendongak dan bilang,'“Katakan dulu, siapa aku? Beritahu itu dulu, lalu, jika aku suka siapa diriku, aku akan naik. Jika tidak, aku akan tinggal di sini hingga aku jadi orang lain lagi—tapi, aduh..." Elisa menangis lagi. “Mengapa tak ada yang menjulurkan kepala mereka mencariku? Aku sudah sangat muak berada di sini seorang diri!”

Seraya ia berkata begitu dilihatnya tangannya, dan terkejut ketika sadar ia sudah mengenakan salah satu sarung tangan si Kelinci. “Bagaimana mungkin sarung tangan ini muat kupakai?” pikirnya. “Aku pasti menciut lagi.”

Elisa bangkit dan menuju ke meja kaca untuk mengukur tinggi badannya, dan ia temukan, sebagaimana telah ia duga, tingginya kini enam puluh senti dan terus menciut dengan cepat sekali. Kemudian ia sadar biang keladinya kali ini adalah kipas yang dipegangnya, maka lekas-lekas ia jatuhkan, tepat sebelum tubuhnya hilang sama sekali.

“Wah, nyaris saja celaka!” ucap Elisa, lumayan takut akibat perubahan terakhir ini, namun sangat senang dirinya masih ada. “Sekarang, ke taman!” Dan berlarilah ia secepat mungkin ke pintu mungil tadi—tapi, sial! Pintu itu sudah terkunci lagi, dan kunci emasnya sudah kembali tergeletak di atas meja. “Semakin lama semakin parah saja,” pikir si anak malang, “tak pernah sebelumnya aku sekecil ini, tidak ketika aku bayi sekalipun! Ini sudah sangat keterlaluan!”

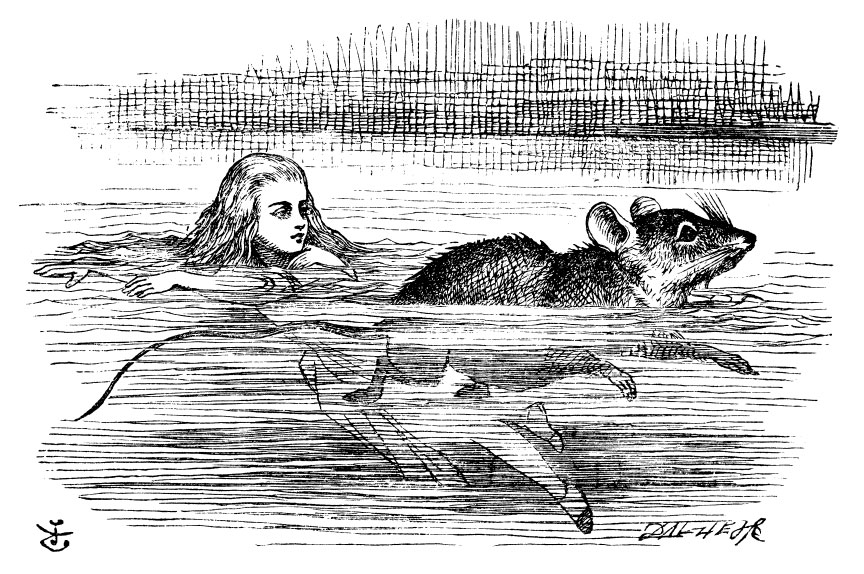

Selesai berucap, tak disangka-sangka Elisa terpeleset, lalu: byur! Ia terbenam hingga dagu dalam air asin. Awalnya ia mengira ia telah, entah bagaimana caranya, jatuh ke laut. “Kalau begitu, aku bisa naik kereta pulang ke rumah,” katanya sendiri. (Elisa pernah satu kali pergi ke pantai, dan setelah itu ia menarik kesimpulan: jika seseorang pergi ke pantai, ia akan temukan beberapa mesin-mandi di laut, anak-anak menggali pasir dengan sekop kayu, sebaris vila dan losmen, dan stasiun kereta api di belakangnya.) Namun, ia lekas menyadari sebenarnya ia tercebur ke dalam kolam airmata hasil tangisannya ketika ia tiga meter tingginya.

“Seandainya aku tadi tidak menangis begitu deras,” desah Elisa, seraya ia berenang-renang mencari jalan keluar. “Sekarang aku tahu rasa, tenggelam dalam airmataku sendiri. Sungguh hukuman yang ajaib! Tapi, segalanya terasa ajaib hari ini.”

Tiba-tiba ia mendengar sesuatu berkecipak beberapa jarak darinya, dan ia berenang mendekati sumber suara itu untuk melihat apa yang terjadi. Awalnya ia pikir pasti singa laut atau kuda nil, tapi kemudian ia ingat betapa kecilnya ia sekarang, dan ia lihat ternyata hanya seekor tikus yang juga tergelincir seperti dirinya.

“Apakah ada gunanya,” pikir Elisa, “bicara pada tikus ini? Semua sangat luar biasa di sini, jadi kukira amat mungkin tikus itu bisa bicara. Lagipula, kan tidak ada salahnya mencoba.”

Maka ia mulai, “Hai, Tikus, tahukah kamu jalan keluar dari kolam ini? Aku sangat lelah berenang-renang.”

Tikus itu memandang Elisa dengan penasaran, dan sepertinya ia mengedipkan salah satu mata kecilnya, namun ia tak berkata apa-apa.

“Mungkin ia tak mengerti bahasaku,” pikir Elisa. “Barangkali ia tikus Prancis yang menumpang ke sini bersama William sang Penakluk (meskipun Elisa banyak mengetahui sejarah, ia tak paham kapan tepatnya sesuatu terjadi). Maka ia mencoba lagi, “Où est ma chatte?” Itu kalimat pertama dalam buku bahasa Prancis-nya.

Sontak tikus tadi melompat dari air dan gemetar ketakutan.

“Oh, maaf,” kata Elisa cepat-cepat, khawatir ia telah melukai perasaan hewan itu. “Aku lupa tikus tidak suka kucing.”

“Tidak suka kucing?” jerit si Tikus dengan suara yang lantang dan penuh emosi. “Kalau kamu jadi tikus, apakah kamu akan suka kucing?”

“Yah, barangkali tidak,” kata Elisa dengan lembut. “Jangan marah ya! Tapi, aku tetap ingin memperkenalkanmu kepada Dinah, kucingku. Kupikir kamu takkan terlalu membenci kucing, seandainya kamu bertemu Dinah. Ia kucing yang pendiam dan penyayang,” lanjut Elisa sambil terus berenang-renang santai di kolam. “Ia suka duduk mengeong di dekat perapian, menjilat-jilat cakarnya dan membersihkan wajahnya, dan tubuhnya terasa sangat lembut ketika kugendong, ia juga sangat mahir menangkap tikus— Eh, maaf,” seru Elisa lagi, sebab kali ini bulu kuduk si Tikus meregang di sekujur tubuhnya, dan Elisa yakin si Tikus pasti sangat tersinggung. “Kita takkan membicarakan Dinah lagi, kalau kamu tak mau,” kata Elisa.

“Memang tak mau,” kata si Tikus yang gemetar dari ujung hidung hingga ujung ekor. “Aku tak pernah mau bicara tentang kucing! Keluarga kami selalu benci kucing—hewan yang kotor dan kasar! Aku tak mau dengar nama mereka lagi.”

“Aku takkan menyebutnya lagi,” kata Elisa, tak sabar mengubah topik pembicaraan. “Apa kamu... apa kamu suka... anjing?”

Si Tikus tidak menjawab. Jadi Elisa meneruskan. “Ada anjing yang sangat ramah di dekat rumah kami, aku ingin memperkenalkannya kepadamu. Seekor terrier bermata cerah dengan bulu coklat keriting panjang. Ia suka menangkap tongkat yang kau lempar, dan bila ingin makan ia akan duduk dan memohon, dan masih banyak hal lain yang bisa dilakukannya. Aku tak ingat apa saja. Ia milik seorang petani, dan si petani bilang anjing itu sangat berguna, ia rela bayar lebih dari seratus pound! Ia juga bilang anjing itu pandai memburu tikus dan— Ya ampun,” seru Elisa penuh penyesalan. “Kamu pasti tersinggung lagi.”

Si Tikus berenang menjauh darinya, sejauh mungkin, dan membuat banyak keributan di kolam seraya ia pergi.

Elisa memanggilnya pelan-pelan, “Tikus! Tikus manis! Ayolah kembali, dan kita takkan bicarakan kucing atau anjing jika kamu tak suka.” Ketika si Tikus mendengar, ia berputar dan berenang perlahan-lahan kembali mendekati Elisa. Wajahnya lumayan pucat (karena semangat, kira Elisa), dan ia bilang dengan suara rendah dan bergetar, “Ayo kita berenang ke tepian! Nanti kuceritakan mengapa aku benci kucing dan anjing, supaya kamu mengerti.”

Memang sudah waktunya pergi, sebab semakin lama kolam semakin ramai, semakin banyak hewan yang jatuh tercebur—ada bebek, burung dodo, burung beo, anak burung elang, dan beberapa makhluk aneh lainnya. Elisa memimpin mereka semua berenang ke tepian.

Terjemahan © Eliza Vitri Handayani.

DOWN THE RABBIT HOLE & THE POOL OF TEARS (from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland)

Lewis Carroll

Alice was beginning to get very tired of sitting by her sister on the bank, and of having nothing to do: once or twice she had peeped into the book her sister was reading, but it had no pictures or conversations in it, 'and what is the use of a book,' thought Alice 'without pictures or conversations?'

So she was considering in her own mind (as well as she could, for the hot day made her feel very sleepy and stupid), whether the pleasure of making a daisy-chain would be worth the trouble of getting up and picking the daisies, when suddenly a White Rabbit with pink eyes ran close by her.

There was nothing so very remarkable in that; nor did Alice think it so very much out of the way to hear the Rabbit say to itself, 'Oh dear! Oh dear! I shall be late!' (when she thought it over afterwards, it occurred to her that she ought to have wondered at this, but at the time it all seemed quite natural); but when the Rabbit actually took a watch out of its waistcoat-pocket, and looked at it, and then hurried on, Alice started to her feet, for it flashed across her mind that she had never before seen a rabbit with either a waistcoat-pocket, or a watch to take out of it, and burning with curiosity, she ran across the field after it, and fortunately was just in time to see it pop down a large rabbit-hole under the hedge.

In another moment down went Alice after it, never once considering how in the world she was to get out again.

The rabbit-hole went straight on like a tunnel for some way, and then dipped suddenly down, so suddenly that Alice had not a moment to think about stopping herself before she found herself falling down a very deep well.

Either the well was very deep, or she fell very slowly, for she had plenty of time as she went down to look about her and to wonder what was going to happen next. First, she tried to look down and make out what she was coming to, but it was too dark to see anything; then she looked at the sides of the well, and noticed that they were filled with cupboards and book-shelves; here and there she saw maps and pictures hung upon pegs. She took down a jar from one of the shelves as she passed; it was labelled 'ORANGE MARMALADE', but to her great disappointment it was empty: she did not like to drop the jar for fear of killing somebody, so managed to put it into one of the cupboards as she fell past it.

'Well!' thought Alice to herself, 'after such a fall as this, I shall think nothing of tumbling down stairs! How brave they'll all think me at home! Why, I wouldn't say anything about it, even if I fell off the top of the house!' (Which was very likely true.)

Down, down, down. Would the fall never come to an end! 'I wonder how many miles I've fallen by this time?' she said aloud. 'I must be getting somewhere near the centre of the earth. Let me see: that would be four thousand miles down, I think—' (for, you see, Alice had learnt several things of this sort in her lessons in the schoolroom, and though this was not a very good opportunity for showing off her knowledge, as there was no one to listen to her, still it was good practice to say it over) '—yes, that's about the right distance—but then I wonder what Latitude or Longitude I've got to?' (Alice had no idea what Latitude was, or Longitude either, but thought they were nice grand words to say.)

Presently she began again. 'I wonder if I shall fall right through the earth! How funny it'll seem to come out among the people that walk with their heads downward! The Antipathies, I think—' (she was rather glad there was no one listening, this time, as it didn't sound at all the right word) '—but I shall have to ask them what the name of the country is, you know. Please, Ma'am, is this New Zealand or Australia?' (and she tried to curtsey as she spoke—fancy curtseying as you're falling through the air! Do you think you could manage it?) 'And what an ignorant little girl she'll think me for asking! No, it'll never do to ask: perhaps I shall see it written up somewhere.'

Down, down, down. There was nothing else to do, so Alice soon began talking again. 'Dinah'll miss me very much to-night, I should think!' (Dinah was the cat.) 'I hope they'll remember her saucer of milk at tea-time. Dinah my dear! I wish you were down here with me! There are no mice in the air, I'm afraid, but you might catch a bat, and that's very like a mouse, you know. But do cats eat bats, I wonder?' And here Alice began to get rather sleepy, and went on saying to herself, in a dreamy sort of way, 'Do cats eat bats? Do cats eat bats?' and sometimes, 'Do bats eat cats?' for, you see, as she couldn't answer either question, it didn't much matter which way she put it. She felt that she was dozing off, and had just begun to dream that she was walking hand in hand with Dinah, and saying to her very earnestly, 'Now, Dinah, tell me the truth: did you ever eat a bat?' when suddenly, thump! thump! down she came upon a heap of sticks and dry leaves, and the fall was over.

Alice was not a bit hurt, and she jumped up on to her feet in a moment: she looked up, but it was all dark overhead; before her was another long passage, and the White Rabbit was still in sight, hurrying down it. There was not a moment to be lost: away went Alice like the wind, and was just in time to hear it say, as it turned a corner, 'Oh my ears and whiskers, how late it's getting!' She was close behind it when she turned the corner, but the Rabbit was no longer to be seen: she found herself in a long, low hall, which was lit up by a row of lamps hanging from the roof.

There were doors all round the hall, but they were all locked; and when Alice had been all the way down one side and up the other, trying every door, she walked sadly down the middle, wondering how she was ever to get out again.

Suddenly she came upon a little three-legged table, all made of solid glass; there was nothing on it except a tiny golden key, and Alice's first thought was that it might belong to one of the doors of the hall; but, alas! either the locks were too large, or the key was too small, but at any rate it would not open any of them. However, on the second time round, she came upon a low curtain she had not noticed before, and behind it was a little door about fifteen inches high: she tried the little golden key in the lock, and to her great delight it fitted!

Alice opened the door and found that it led into a small passage, not much larger than a rat-hole: she knelt down and looked along the passage into the loveliest garden you ever saw. How she longed to get out of that dark hall, and wander about among those beds of bright flowers and those cool fountains, but she could not even get her head through the doorway; 'and even if my head would go through,' thought poor Alice, 'it would be of very little use without my shoulders. Oh, how I wish I could shut up like a telescope! I think I could, if I only knew how to begin.' For, you see, so many out-of-the-way things had happened lately, that Alice had begun to think that very few things indeed were really impossible.

There seemed to be no use in waiting by the little door, so she went back to the table, half hoping she might find another key on it, or at any rate a book of rules for shutting people up like telescopes: this time she found a little bottle on it, ('which certainly was not here before,' said Alice,) and round the neck of the bottle was a paper label, with the words 'DRINK ME' beautifully printed on it in large letters.

It was all very well to say 'Drink me,' but the wise little Alice was not going to do that in a hurry. 'No, I'll look first,' she said, 'and see whether it's marked "poison" or not'; for she had read several nice little histories about children who had got burnt, and eaten up by wild beasts and other unpleasant things, all because they would not remember the simple rules their friends had taught them: such as, that a red-hot poker will burn you if you hold it too long; and that if you cut your finger very deeply with a knife, it usually bleeds; and she had never forgotten that, if you drink much from a bottle marked 'poison,' it is almost certain to disagree with you, sooner or later.

However, this bottle was not marked 'poison,' so Alice ventured to taste it, and finding it very nice, (it had, in fact, a sort of mixed flavour of cherry-tart, custard, pine-apple, roast turkey, toffee, and hot buttered toast,) she very soon finished it off.

* * * * *

* * * *

* * * * *

'What a curious feeling!' said Alice; 'I must be shutting up like a telescope.'

And so it was indeed: she was now only ten inches high, and her face brightened up at the thought that she was now the right size for going through the little door into that lovely garden. First, however, she waited for a few minutes to see if she was going to shrink any further: she felt a little nervous about this; 'for it might end, you know,' said Alice to herself, 'in my going out altogether, like a candle. I wonder what I should be like then?' And she tried to fancy what the flame of a candle is like after the candle is blown out, for she could not remember ever having seen such a thing.

After a while, finding that nothing more happened, she decided on going into the garden at once; but, alas for poor Alice! when she got to the door, she found she had forgotten the little golden key, and when she went back to the table for it, she found she could not possibly reach it: she could see it quite plainly through the glass, and she tried her best to climb up one of the legs of the table, but it was too slippery; and when she had tired herself out with trying, the poor little thing sat down and cried.

'Come, there's no use in crying like that!' said Alice to herself, rather sharply; 'I advise you to leave off this minute!' She generally gave herself very good advice, (though she very seldom followed it), and sometimes she scolded herself so severely as to bring tears into her eyes; and once she remembered trying to box her own ears for having cheated herself in a game of croquet she was playing against herself, for this curious child was very fond of pretending to be two people. 'But it's no use now,' thought poor Alice, 'to pretend to be two people! Why, there's hardly enough of me left to make one respectable person!'

Soon her eye fell on a little glass box that was lying under the table: she opened it, and found in it a very small cake, on which the words 'EAT ME' were beautifully marked in currants. 'Well, I'll eat it,' said Alice, 'and if it makes me grow larger, I can reach the key; and if it makes me grow smaller, I can creep under the door; so either way I'll get into the garden, and I don't care which happens!'

She ate a little bit, and said anxiously to herself, 'Which way? Which way?', holding her hand on the top of her head to feel which way it was growing, and she was quite surprised to find that she remained the same size: to be sure, this generally happens when one eats cake, but Alice had got so much into the way of expecting nothing but out-of-the-way things to happen, that it seemed quite dull and stupid for life to go on in the common way.

So she set to work, and very soon finished off the cake.

* * * * *

* * * *

* * * * *

'Curiouser and curiouser!' cried Alice (she was so much surprised, that for the moment she quite forgot how to speak good English); 'now I'm opening out like the largest telescope that ever was! Good-bye, feet!' (for when she looked down at her feet, they seemed to be almost out of sight, they were getting so far off). 'Oh, my poor little feet, I wonder who will put on your shoes and stockings for you now, dears? I'm sure I shan't be able! I shall be a great deal too far off to trouble myself about you: you must manage the best way you can;—but I must be kind to them,' thought Alice, 'or perhaps they won't walk the way I want to go! Let me see: I'll give them a new pair of boots every Christmas.'

And she went on planning to herself how she would manage it. 'They must go by the carrier,' she thought; 'and how funny it'll seem, sending presents to one's own feet! And how odd the directions will look!

Alice's Right Foot, Esq. Hearthrug, near The Fender, (with Alice's love).

Oh dear, what nonsense I'm talking!'

Just then her head struck against the roof of the hall: in fact she was now more than nine feet high, and she at once took up the little golden key and hurried off to the garden door.

Poor Alice! It was as much as she could do, lying down on one side, to look through into the garden with one eye; but to get through was more hopeless than ever: she sat down and began to cry again.

'You ought to be ashamed of yourself,' said Alice, 'a great girl like you,' (she might well say this), 'to go on crying in this way! Stop this moment, I tell you!' But she went on all the same, shedding gallons of tears, until there was a large pool all round her, about four inches deep and reaching half down the hall.

After a time she heard a little pattering of feet in the distance, and she hastily dried her eyes to see what was coming. It was the White Rabbit returning, splendidly dressed, with a pair of white kid gloves in one hand and a large fan in the other: he came trotting along in a great hurry, muttering to himself as he came, 'Oh! the Duchess, the Duchess! Oh! won't she be savage if I've kept her waiting!' Alice felt so desperate that she was ready to ask help of any one; so, when the Rabbit came near her, she began, in a low, timid voice, 'If you please, sir—' The Rabbit started violently, dropped the white kid gloves and the fan, and skurried away into the darkness as hard as he could go.

Alice took up the fan and gloves, and, as the hall was very hot, she kept fanning herself all the time she went on talking: 'Dear, dear! How queer everything is to-day! And yesterday things went on just as usual. I wonder if I've been changed in the night? Let me think: was I the same when I got up this morning? I almost think I can remember feeling a little different. But if I'm not the same, the next question is, Who in the world am I? Ah, that's the great puzzle!' And she began thinking over all the children she knew that were of the same age as herself, to see if she could have been changed for any of them.

'I'm sure I'm not Ada,' she said, 'for her hair goes in such long ringlets, and mine doesn't go in ringlets at all; and I'm sure I can't be Mabel, for I know all sorts of things, and she, oh! she knows such a very little! Besides, she's she, and I'm I, and—oh dear, how puzzling it all is! I'll try if I know all the things I used to know. Let me see: four times five is twelve, and four times six is thirteen, and four times seven is—oh dear! I shall never get to twenty at that rate! However, the Multiplication Table doesn't signify: let's try Geography. London is the capital of Paris, and Paris is the capital of Rome, and Rome—no, that's all wrong, I'm certain! I must have been changed for Mabel! I'll try and say "How doth the little—"' and she crossed her hands on her lap as if she were saying lessons, and began to repeat it, but her voice sounded hoarse and strange, and the words did not come the same as they used to do:—

'How doth the little crocodile Improve his shining tail, And pour the waters of the Nile On every golden scale! 'How cheerfully he seems to grin, How neatly spread his claws, And welcome little fishes in With gently smiling jaws!'

'I'm sure those are not the right words,' said poor Alice, and her eyes filled with tears again as she went on, 'I must be Mabel after all, and I shall have to go and live in that poky little house, and have next to no toys to play with, and oh! ever so many lessons to learn! No, I've made up my mind about it; if I'm Mabel, I'll stay down here! It'll be no use their putting their heads down and saying "Come up again, dear!" I shall only look up and say "Who am I then? Tell me that first, and then, if I like being that person, I'll come up: if not, I'll stay down here till I'm somebody else"—but, oh dear!' cried Alice, with a sudden burst of tears, 'I do wish they would put their heads down! I am so very tired of being all alone here!'

As she said this she looked down at her hands, and was surprised to see that she had put on one of the Rabbit's little white kid gloves while she was talking. 'How can I have done that?' she thought. 'I must be growing small again.' She got up and went to the table to measure herself by it, and found that, as nearly as she could guess, she was now about two feet high, and was going on shrinking rapidly: she soon found out that the cause of this was the fan she was holding, and she dropped it hastily, just in time to avoid shrinking away altogether.

'That was a narrow escape!' said Alice, a good deal frightened at the sudden change, but very glad to find herself still in existence; 'and now for the garden!' and she ran with all speed back to the little door: but, alas! the little door was shut again, and the little golden key was lying on the glass table as before, 'and things are worse than ever,' thought the poor child, 'for I never was so small as this before, never! And I declare it's too bad, that it is!'

As she said these words her foot slipped, and in another moment, splash! she was up to her chin in salt water. Her first idea was that she had somehow fallen into the sea, 'and in that case I can go back by railway,' she said to herself. (Alice had been to the seaside once in her life, and had come to the general conclusion, that wherever you go to on the English coast you find a number of bathing machines in the sea, some children digging in the sand with wooden spades, then a row of lodging houses, and behind them a railway station.) However, she soon made out that she was in the pool of tears which she had wept when she was nine feet high.

'I wish I hadn't cried so much!' said Alice, as she swam about, trying to find her way out. 'I shall be punished for it now, I suppose, by being drowned in my own tears! That will be a queer thing, to be sure! However, everything is queer to-day.'

Just then she heard something splashing about in the pool a little way off, and she swam nearer to make out what it was: at first she thought it must be a walrus or hippopotamus, but then she remembered how small she was now, and she soon made out that it was only a mouse that had slipped in like herself.

'Would it be of any use, now,' thought Alice, 'to speak to this mouse? Everything is so out-of-the-way down here, that I should think very likely it can talk: at any rate, there's no harm in trying.' So she began: 'O Mouse, do you know the way out of this pool? I am very tired of swimming about here, O Mouse!' (Alice thought this must be the right way of speaking to a mouse: she had never done such a thing before, but she remembered having seen in her brother's Latin Grammar, 'A mouse—of a mouse—to a mouse—a mouse—O mouse!') The Mouse looked at her rather inquisitively, and seemed to her to wink with one of its little eyes, but it said nothing.

'Perhaps it doesn't understand English,' thought Alice; 'I daresay it's a French mouse, come over with William the Conqueror.' (For, with all her knowledge of history, Alice had no very clear notion how long ago anything had happened.) So she began again: 'Ou est ma chatte?' which was the first sentence in her French lesson-book. The Mouse gave a sudden leap out of the water, and seemed to quiver all over with fright. 'Oh, I beg your pardon!' cried Alice hastily, afraid that she had hurt the poor animal's feelings. 'I quite forgot you didn't like cats.'

'Not like cats!' cried the Mouse, in a shrill, passionate voice. 'Would you like cats if you were me?'

'Well, perhaps not,' said Alice in a soothing tone: 'don't be angry about it. And yet I wish I could show you our cat Dinah: I think you'd take a fancy to cats if you could only see her. She is such a dear quiet thing,' Alice went on, half to herself, as she swam lazily about in the pool, 'and she sits purring so nicely by the fire, licking her paws and washing her face—and she is such a nice soft thing to nurse—and she's such a capital one for catching mice—oh, I beg your pardon!' cried Alice again, for this time the Mouse was bristling all over, and she felt certain it must be really offended. 'We won't talk about her any more if you'd rather not.'

'We indeed!' cried the Mouse, who was trembling down to the end of his tail. 'As if I would talk on such a subject! Our family always hated cats: nasty, low, vulgar things! Don't let me hear the name again!'

'I won't indeed!' said Alice, in a great hurry to change the subject of conversation. 'Are you—are you fond—of—of dogs?' The Mouse did not answer, so Alice went on eagerly: 'There is such a nice little dog near our house I should like to show you! A little bright-eyed terrier, you know, with oh, such long curly brown hair! And it'll fetch things when you throw them, and it'll sit up and beg for its dinner, and all sorts of things—I can't remember half of them—and it belongs to a farmer, you know, and he says it's so useful, it's worth a hundred pounds! He says it kills all the rats and—oh dear!' cried Alice in a sorrowful tone, 'I'm afraid I've offended it again!' For the Mouse was swimming away from her as hard as it could go, and making quite a commotion in the pool as it went.

So she called softly after it, 'Mouse dear! Do come back again, and we won't talk about cats or dogs either, if you don't like them!' When the Mouse heard this, it turned round and swam slowly back to her: its face was quite pale (with passion, Alice thought), and it said in a low trembling voice, 'Let us get to the shore, and then I'll tell you my history, and you'll understand why it is I hate cats and dogs.'

It was high time to go, for the pool was getting quite crowded with the birds and animals that had fallen into it: there were a Duck and a Dodo, a Lory and an Eaglet, and several other curious creatures. Alice led the way, and the whole party swam to the shore.