Cukup Sendiri

Elizabeth Flux

Diterjemahkan oleh Nicolaus Gogor Seta Dewa

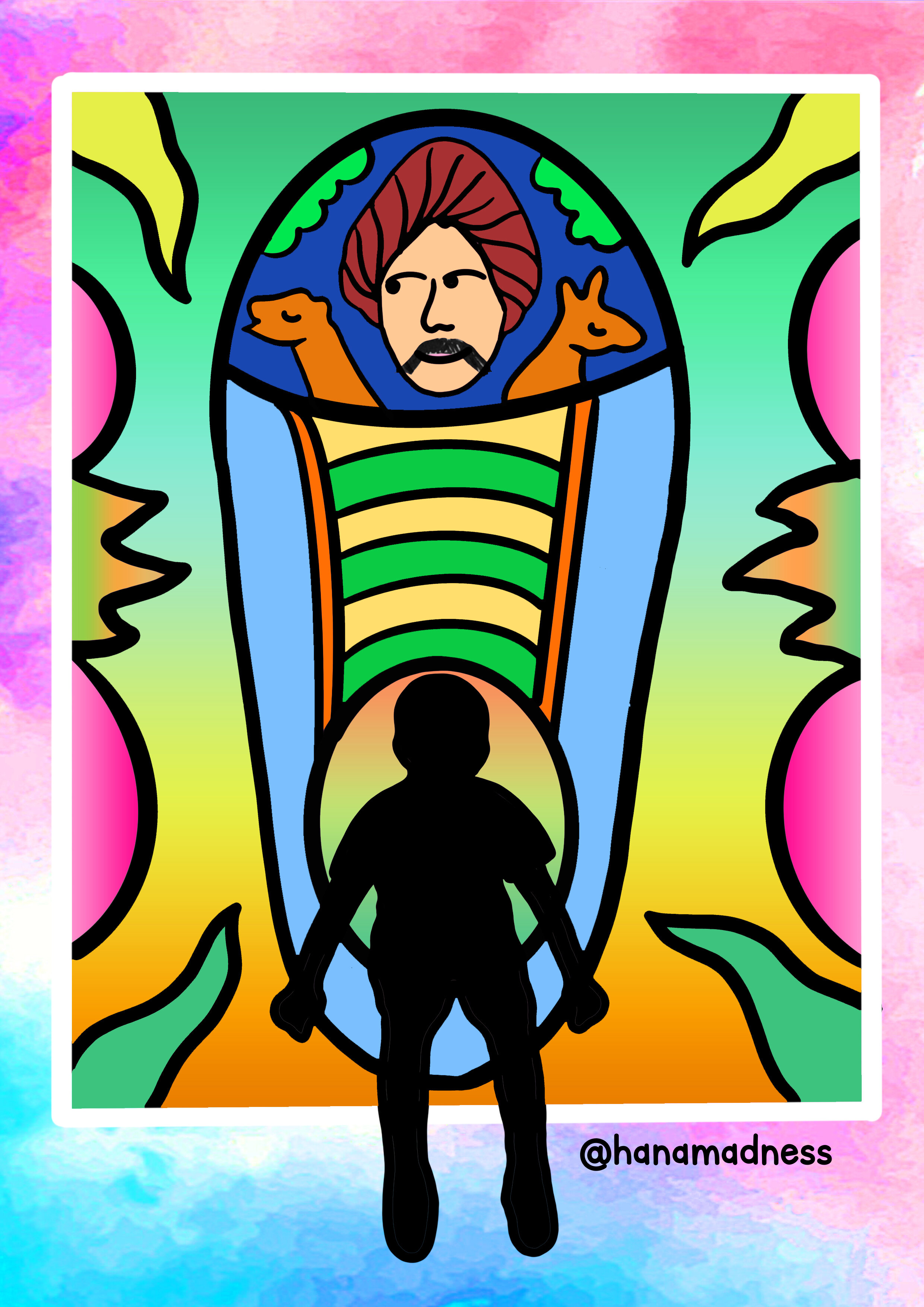

Ilustrasi oleh Hana Madness

Ketika mereka turun dari pesawat, ibu Zhen berbalik untuk memegang tangannya dan mendapati dua versi putranya yang berbeda. Dia mendecakkan lidahnya dengan tidak sabar. Dia masih harus mengambil tas-tas dan mengisi dokumen—dia tidak punya waktu untuk realisme magis. Sambil menggandeng tangan keduanya saat berjalan menuruni tangga reyot, dia mendesah dalam bahasa yang mengingatkannya akan rumah.

"Tenangkan dirimu," katanya. Dengan malu-malu, Si Anak Baru menghilang, dan Zhen menjadi satu orang lagi.

Dia menunggu dengan sabar ketika seorang petugas bea cukai laki-laki merogoh koper ibunya, mengambil barang-barang satu per satu dan menatap mereka dengan saksama. Saat melongok ke dalam satu kantong plastik, mata laki-laki itu menyala sebentar sebelum memandang kecewa; dia menemukan paket teh yang boleh dibawa dalam perjalanan udara, bukan buah atau daging kering seperti yang dia harapkan. Seorang laki-laki berambut pirang dengan santai melemparkan tasnya ke meja sebelah dan seorang petugas bea cukai perempuan hanya membuka resleting bagian atas sebelum menyuruhnya lanjut. Petugas bea cukai yang pertama melanjutkan pemeriksaan ke penanak nasi mereka. Dengan seragam biru dan lencana emasnya, dia terlihat seperti polisi dari komik tentang orang-orang Australia terkenal yang dibagikan kepada anak-anak di pesawat. Zhen melihat ibunya tersentak, tapi tidak mengatakan apa-apa ketika penanak nasi itu dirakit lagi seenaknya sebelum mereka dibiarkan lanjut ditambahi gerutuan kecil dan ucapan kosong “nikmati kunjungan Anda”.

"Oh, kami akan tinggal di sini," ibunya tertawa, menatap mata petugas bea cukai itu.

"Baik," katanya acuh tak acuh, menunjuk kami ke baris berikutnya.

Ibunya mendorong Zhen jalan ke depan dan mereka buru-buru keluar dari bandara, melewati poster-poster keluarga pirang yang sedang tersenyum berpiknik di pantai. Dia membawa boneka beruang hitam yang hampir sebesar tubuhnya, dan ketika dia memegang kaki boneka itu di tangannya, sambil bergegas mengejar ibunya, dia mencoba membayangkan dirinya sendiri dan Beruang di tempat pasangan itu berpose, terjebak selamanya saling menyentuhkan gelas anggur dengan lautan sebagai latar belakang.

Pada hari pertamanya di sekolah baru, dia salah memakai sepatu. Saat berbaris di luar kelas, sepatu kets Zhen langsung tampak menonjol di antara barisan sepatu putih. "Terlalu berwarna" kata pesan yang dikirim oleh gurunya untuk diperlihatkan kepada orangtuanya. "Dan kebijakan seragam menganjurkan tali daripada Velcro." Saat mengabsen, mereka dengan hati-hati mengumumkan nama belakangnya, bingung karena urutan dan campuran huruf yang asing.

"John," dia membenarkan, menyebut nama yang dipilihnya dari daftar kecil yang dibuat oleh orangtuanya. Pada saat itulah gurunya memperhatikan sepatu itu.

"Baik," katanya ragu-ragu.

Orangtuanya memperdebatkan apakah bijaksana membeli sepasang sepatu lagi. Lalu mereka memutuskan untuk tidak melakukannya. Tidak praktis.

"Sepatunya akan kekecilan dalam enam bulan," kata ayahnya. Zhen terbelah dua lagi, dan dirinya yang baru menendang sepatu kets pembuat keributan itu.

"Kamu berlebihan," ujar ayahnya. “Dan apa kata ibumu soal penggandaan diri yang terus-menerus kamu lakukan ini?” Zhen yang duduk di sofa mengangkat telapak tangannya, meminta maaf. Dirinya yang lain, yang pendiam dan cemberut menghilang lagi. Orangtuanya menyalakan berita dan Zhen duduk diam, membaca buku komik kecil, berusaha menghafalkan kisah Monga dan menyesuaikan dirinya sendiri pada negara baru mereka yang sama.

Dia sudah selesai membacanya, tapi terus kembali ke tiga halaman yang sama, gambar wajah yang sama. Monga tidak terlihat seperti orang dari negara asalnya, tapi dia juga tidak terlihat seperti orang-orang di tempat tinggalnya yang baru. Zhen terpesona. Orangtuanya tidak membiarkannya membawa komik itu ke sekolah—bagaimana kau bisa belajar jika kau hanya membaca hal yang sama berulang-ulang?—sehingga dia dengan susah payah menggambar wajah Monga dua kali: satu di ujung setiap sepatunya.

Anak-anak di sekolah mengaguminya, tapi rumit menjelaskan siapa tokoh itu. Ketika dia memberitahu mereka bahwa dia orang Australia, mereka mencibir, dan ketika dia mengatakan nama tokoh itu Monga, anak-anak lain terpingkal-pingkal.

"MONG-a?" seru teman sekelasnya, Cody. "Kau menggambar mong di sepatumu?"

"Masuk akal," tambah Lachy, menarik sudut matanya. "Mong yang menggambar Mong."

Julukan itu melekat padanya.

Sebelum sekolah dimulai tahun itu, orangtuanya menerima daftar buku dan beberapa saran untuk kebutuhan harian anak mereka.

Sepatu olahraga untuk pelajaran olahraga dan untuk bermain di bak pasir.

Kotak buah untuk istirahat.

Sesuatu untuk kegiatan Show ’n Tell, yaitu menunjukkan barang dan menceritakannya.

Mereka adalah keluarga yang berbahasa Inggris, meskipun Zhen dan ibunya bisa bicara dwibahasa. Waktu itu sepuluh tahun terlalu awal untuk internet, dan untuk berteman dengan tetangga mereka, ayahnya mencoba memakai kamus yang, mengherankannya, tidak membantu sama sekali.

Pada waktu istirahat, Zhen membuka kotak makan siangnya yang penuh dengan irisan buah persik, pisang, dan lengkeng kalengan sementara anak-anak lain menusukkan sedotan ke minuman kotakan, menyedot isinya cepat-cepat—saling berlomba.

"Apa itu, Mong?" tanya Cody.

"Kotak buahku?" jawab Zhen, setelah diam sejenak.

Tawa terbahak-bahak dan cemoohan mengikutinya saat dia berjalan menuju sudut bak pasir yang kosong, lalu menjatuhkan dirinya, sendirian.

Mou mo! Wu zhou lat tat! Jangan sentuh! Itu kotor! teriak ibunya di benaknya.

Nasihat bayangan itu benar; pasir itu mungkin penuh dengan kuman, tapi dengan hati-hati dia mulai menggali dengan satu kaki, lalu dengan kaki yang lain, kemudian meraih sekepal pasir dan menumpuknya di atas sepatunya. Setengah tenggelam, warna dan wajah Monga segera terkubur oleh longsoran pasir lembut.

Dalam komik itu, Monga hanyalah satu dari banyak orang lain yang hidup di tempat yang dibaca Zhen sebagai Australia yang Sebenarnya. Ada lautan yang berkilauan, ada padang-padang raksasa—dan hamparan pasir kuning dan oranye yang lembut membuat laut palsu yang lebih luas daripada apapun yang pernah dia saksikan. Yang tidak ada adalah gedung-gedung pencakar langit seperti di tempat tinggalnya yang dulu, jalanan yang dipadati orang. Setiap Sabtu pagi yang diingatnya dulu, Ah Poh selalu datang menjemputnya dan mereka menjelajahi pasar bersama. Neneknya kejam bila menawar harga, dengan cepat menyebutkan daftar apa saja yang ingin dia beli bersama dengan harga tawarannya—bahasa mereka yang terdiri dari banyak kata dengan hanya satu suku kata membuat percakapan itu terdengar seperti senapan mesin bahasa.

Rumah baru mereka terasa lebih lambat; orang-orang menikmati bunyi seperti John menikmati leci yang Ah Poh kupas dan jejalkan di mulutnya agar dia tidak mengeluh ketika perjalanan mereka terlalu panjang. Toko-toko di sini berbeda; bersih dan tenang. Tidak ada peti bocor yang meneteskan lelehan es dan sisik ikan di lantai yang licin. Orang-orang tidak berbicara, mereka hanya berjalan lurus naik turun, menumpuk-numpuk plastik dan kardus di troli mereka.

Monga terbenam di pasir sepenuhnya, lalu bel berbunyi. Zhen merasa dirinya terbelah dua lagi, tapi kali ini tidak ada yang mengomelinya.

Si Anak Baru berdiri dan mengikuti teman-teman sekelasnya ke ruang sekolah. Zhen tinggal di pasir, merenungi sepatunya.

Selama minggu-minggu berikutnya, Zhen kadang tunggal dan kadang ganda—membuat orangtua dan gurunya dongkol. Ayahnya menggerutu saat dia dipaksa lagi memompa kasur tiup untuk menanggung "kekonyolan ini". Si Anak Baru hanya tersenyum dan bermain dengan Tazos-nya. Zhen mengabaikannya. Dia membawa surat teguran sopan lain setelah para guru akhirnya melihat gambar itu, dan dia sekarang menggambar Monga lagi, kali ini di sol sepatu putih barunya sehingga tidak ada yang melihat.

Dia duduk, atau kadang-kadang mereka duduk, setiap hari Rabu ketika semua siswa di kelasnya bergiliran maju untuk Show n’ Tell. Ada yang membawa biji pinus dan piala kakak laki-laki, kaset VHS kartun Disney, atau potongan tiket sepak bola akhir pekan. Ketika Zhen mengangkat tangannya untuk bertanya mengapa bola milik teman sekelas berbentuk panjang dan bukan bulat, wajah Si Anak Baru memerah dan dia bergeser menjauh.

Ketika minggu gilirannya tiba, Zhen tidak perlu berpikir dua kali. Dia memasukkan komik dengan hati-hati di antara dua buku latihan sehingga tidak akan terlipat di tasnya, dan saat tiba di ruang kelas, dia menyelipkan ranselnya di tempat biasa: di atas papan namanya yang telah dihias dengan ceria oleh gurunya dengan stiker wombat, di antara Hannah (burung emu) dan Lachy (bilby).

Zhen lebih bersemangat hari itu daripada setahun belakangan; dia masih dipanggil "Mong" oleh sebagian besar teman sekelasnya, yang tampaknya sudah lupa dari mana asal nama itu. Ketika ditanya, dia diam saja soal gambar rahasia yang perlahan memudar seraya dia berjalan dari kelas ke kelas dan berlarian saat bermain kejar-kejaran sesekali.

"Aku membawa komikku," katanya kepada mejanya, saat duduk sebelum diabsen. "Ada di tasku. Kalian semua bisa melihatnya setelah makan siang." Cody, yang duduk di seberangnya menatapnya. "Kenapa? Kami tidak akan bisa membacanya." Zhen menatap Cody sebentar, sebelum ingatan tubuhnya menarik pandangannya kembali ke meja—tapi dia masih bisa melihat bocah itu dari sudut matanya, berkasak-kusuk dan terkikik dengan para penghuni meja yang lain. Dia merasakan dirinya membelah lagi, dan Si Anak Baru bergabung ikut tertawa dengan anak-anak lain. Zhen tetap diam, matanya tertuju ke meja, menggesekkan sepatu kirinya ke lantai linoleum.

Anak-anak lain kebanyakan tidak tertarik pada Zhen. Dia tidak membuat mereka terkesan saat olahraga, dan bukan yang terbaik dalam hal-hal lain yang tampaknya penting: menggambar garis paling lurus atau memiliki stiker terbanyak di tabel buku. Dia tahu alfabet, tapi dia menyanyikan lagu-lagu yang berbeda di taman kanak-kanak di negeri asalnya dulu, jadi dia tidak hafal lirik lagu-lagu yang mereka nyanyikan setiap pagi. Jika mereka memperhatikannya, itu biasanya untuk menunjukkan kesalahan yang dia lakukan: mengikat tali sepatu dengan bentuk satu lingkaran, bukan telinga kelinci; mengucapkan kata-kata dengan berbeda; tidak tahu perbedaan antara gaun dan rok.

Saat makan siang, Zhen pergi ke petak rumputnya yang biasa. Dia baru saja memasukkan sendok ke dalam termosnya ketika dua gadis dari mejanya berlari, antara kesal dan tertawa. “Cody membaca komikmu,” kata salah satu dari mereka, sambil terkikik. "Kupikir kamu harus tahu." Mereka pergi, mata Zhen mengikuti mereka, lalu mendahului, memandang ke rak ransel tempat Cody dan beberapa teman berjongkok melihat sesuatu.

Mereka sudah pergi saat Zhen sampai ke tasnya, yang terbuka. Komik itu didorong masuk dengan kasar di bagian atas, tidak lagi dilindungi oleh buku latihan. Setiap halamannya kusut, sebagian robek menjadi dua. Si Anak Baru masuk ke ruang kelas dan duduk sendirian di mejanya, perlahan menggerakkan jari-jarinya di atas halaman-halaman yang rusak. Zhen tetap di dekat tasnya, dalam diam menatap bukunya yang hancur, sebelum mengepalkan tinjunya dan mendekati Cody.

Zhen tetap ganda.

Pada awalnya semua baik-baik saja. Ketika sudah jelas bahwa pemisahan diri itu permanen, ayahnya dengan enggan membeli tempat tidur baru. Untuk menghindari kebingungan, keluarganya memutuskan untuk memanggil Si Anak Baru John. John dan Zhen mulanya sangat mirip, melakukan kegiatan yang sama saat pulang sekolah dan berbicara dalam bahasa yang tidak dimengerti oleh orang lain ketika mereka ingin membicarakan rahasia selama di kelas. Sisi kamar mereka mulai berbeda sedikit demi sedikit; sisi kamar Zhen diisi dengan sertifikat-sertifikat yang menunjukkan bakat matematika dan sains, sedangkan sisi kamar John dihiasi piala olahraga dan CD.

"Kalian terlalu harfiah," tegur ayah mereka ketika Zhen diam-diam makan ikan dengan orangtuanya sementara John duduk di kamar lain, gusar karena dia tidak diizinkan pergi ke pesta menginap yang bersamaan dengan festival yang tidak dirayakan oleh orang lain.

Mereka duduk berdampingan pada tengah malam, di rumah tempat mereka tinggal selama hampir sepuluh tahun, pandangan terpaku pada televisi—menyaksikan kedua menara itu runtuh setelah menerima telepon panik dari Ah Poh. Ibu mereka pulang dari kerja keesokan harinya dan dengan lirih menceritakan bahwa seorang rekan kerja bertanya kepadanya apakah dia sudah "mendengar berita itu".

"Iya. Kami menyaksikannya ketika itu terjadi," jawabnya.

"Mengerikan sekali," kata perempuan itu. "Tapi orang-orang kalian tidak seperti itu."

Wajah Zhen menegang, sementara di sebelahnya, John tampak tidak mendengar, terlalu asyik dengan buku Paul Jennings yang dia pinjam dari perpustakaan.

Sebulan sekali, ibu mereka menelepon Ah Poh. Setelah membicarakan keluhan kesehatan dan daftar makanan yang mereka makan hari itu, Ah Poh memarahi putrinya karena membiarkan Zhen terbelah menjadi dua orang berbeda, menyalahkan makanan dan perihal dia tidak cukup di rumah. Lalu telepon akan diserahkan kepada kedua anak laki-laki untuk menjawab pertanyaan tentang sekolah; apakah mereka makan cukup; kapan mereka akan datang berkunjung. Pada awalnya, John dan Zhen bergiliran menjawab. Namun, akhirnya, lama-kelamaan John akan membuat alasan; pekerjaan rumah, kelelahan, apa pun, untuk menghindari berbicara di telepon, dan Zhen dan Ah Poh akan dibiarkan sendirian, bersahut-sahutan.

Seiring berjalannya waktu, panggilan telepon semakin sedikit dan jarang. Meski begitu, butuh waktu lama bagi Zhen untuk menyadari bahwa orang-orang telah berhenti melihatnya sama sekali; bahkan lebih lama baginya untuk menyadari bahwa John yang melakukan ini kepadanya. Suatu hari dia pulang dari sekolah dan melihat tempat tidurnya sudah dikemas dan dimasukkan ke garasi. Ketika dia berbalik untuk kembali ke rumah, tangannya menembus gagang pintu.

John tidak mau memberinya penjelasan. Dia menjerit, berteriak, dan memohon, tapi wujud fisiknya pura-pura tidak mendengar. Zhen tenggelam ke tanah, dan menemukan dirinya terseret di belakang John, sebuah dinding tak terlihat mencegahnya mendekat kurang dari sepuluh meter.

"Uhh, diam, Mong," adalah satu-satunya ucapan John kepadanya selama enam bulan dalam kesendirian. Dia tidak bisa ingat seperti apa rupa Monga; buku kusut itu masih dijejalkan di raknya, tapi halamannya tidak dapat dibalik dengan tangannya yang memudar.

Butuh beberapa tahun, tapi Zhen telah terbiasa dengan keheningan. Dia berbaring diam, memperhatikan dirinya membalas dengan bahasa Inggris pertanyaan ibunya yang menggunakan bahasa kampung halaman, menyaksikan dirinya tak mau lagi membawa sisa makanan ke sekolah.

Dia melihat alat kaligrafi yang diberi Ah Poh menjadi berdebu, dipindahkan ke belakang piala-piala dan akhirnya menetap di belakang lemari, segel lilin pada tintanya tidak pernah rusak, sementara cairannya perlahan mengering, menjadi residu; tidak dapat digunakan lagi.

Dia mengisi kesepian panjangnya dengan melukis gambar yang tak terlihat; kamarnya menjadi pasar seraya dia menyelusuri jarinya sepanjang dinding, menciptakan peti dan kandang serta tokoh-tokoh yang tidak lebih nyata daripada dia, menghilang sentimeter demi sentimeter di belakangnya. Saat-saat ketika dia merasa terlihat makin jarang, dan dia tidak tahu apakah itu hanya bayangan putus asanya.

Dalam panggilan telepon bulanan mereka, Ah Poh memberi selamat kepada ibu John karena akhirnya berhasil menemani John melewati fasenya, meskipun, ketika telepon diserahkan kepada John, kekecewaan Ah Poh saat mendengar dui mm zhi, mm ming bak sangat terasa.

"Biarkan aku bicara," pinta Zhen. "Aku bisa membantu."

Zhoi gein. Selamat tinggal. Sampai jumpa lagi. John menutup telepon.

Hari itu adalah hari libur universitas dan Zhen menyaksikan teman-temannya yang tidak pernah bertemu dengannya duduk mengelilingi sebuah meja, kian menjadi mabuk dengan setiap putaran permainan minum yang terus berlangsung. Lingkaran kartu mengelilingi kendi berisi campuran minuman dan Zhen melihat dirinya menarik kartu as.

"ATURAN BARU!" pekik kelompok itu. Tapi mereka kebingungan; bergairah tapi tumpul karena alkohol, mereka tidak tahu cara mengendalikan diri. Suasana hening.

Seorang anak lelaki dengan kulit agak lebih gelap daripada yang lain mencuri pandang ke arah John ketika dia duduk, menyeret jari telunjuknya di sepanjang tepi kartu, menunggu.

"Aku tahu," katanya sambil tersenyum. “Kita semua harus berbicara dalam bahasa ibu kita. Atau minum. "

Zhen mendapati dirinya duduk di tempat John, kartu itu sekarang berada di tangannya. Orang-orang menatapnya. Dia menggumamkan sebuah kalimat dengan suaranya yang panjang dan lirih, diucapkan dengan sempurna. Teman-temannya tertawa dan melanjutkan menarik kartu. Zhen tersenyum, dan di belakangnya, di sudut, John sangat marah. Ketika raja terakhir ditarik, mengakhiri permainan itu, teriakan mengembalikan posisi mereka seperti sebelumnya dan keduanya duduk cemberut dalam diam: yang satu penuh dengan kemarahan, yang lain merasa hampa.

Ah Poh berkunjung pada saat yang paling buruk—dalam periode antara akhir ujian dan menunggu hasil. John gugup, khawatir gagal dalam tahun saat dia tidak lagi punya rutinitas seperti waktu sekolah dulu dan kemalasannya pun terungkap.

"Vi-sit," ucapnya melafalkan saat mereka bicara di telepon.

"Fisit," balas Ah Poh. "Fisit?" Bahasa mereka tidak punya huruf V.

Hou loi mei gein.

John duduk di samping dirinya sendiri di tempat duduk belakang mobil, melihat lutut Zhen naik turun saat dia menatap keluar jendela. Ayah mereka menemukan sebuah taman di dekat pintu masuk dan mereka semua keluar. Mereka melihat poster Monga itu bersamaan. Dari sudut matanya, John bisa melihat Zhen menunduk mengingat sepatu warna-warni yang sudah lama dibuang, lalu mundur lagi, membandingkan. Dia mengedip, berpaling dari Zhen, lalu menatap lurus ke arah wajah yang tidak pernah dia lihat sejak dia menyelipkan komik kusut di antara dua buku tebal, mengernyit ketika buku-buku jarinya yang memar menyentuh punggung buku-buku itu.

Dui mm ji katanya, kata-katanya kaku, formal, dan tidak terdengar.

Maaf, katanya, pada dirinya sendiri, dan tidak kepada siapa pun.

© Elizabeth Flux

English translation © Nicolaus Gogor Seta Dewa

ONE’S COMPANY

Elizabeth Flux

As they stepped off the plane, Zhen’s mother turned to hold his hand and was met with two different versions of her son. She tsk’d impatiently. There were bags to collect and paperwork to fill out—she didn’t have time for magical realism. Grabbing each one of them by the hand as they made their way down the rickety stairs, she sighed in the language of what used to be home.

“Pull yourself together,” she said. Sheepishly, the new one disappeared, and Zhen was one person again.

He waited patiently as the customs man dug through his mother’s suitcase, taking things out one by one and peering at them intently. Looking in one plastic bag, the man’s eyes briefly lit up before disappointment settled in; he’d discovered air-travel-approved packets of tea, and not the dried fruit or meat he was expecting. A fair-haired man casually tossed down his bag at the next table, and the woman barely unzipped the top before waving him along. The customs man moved onto their rice cooker. With his blue uniform and gold badge he looked like the policeman from the comics about famous Australians they’d handed out to the children on the plane. Zhen saw his mother flinch but say nothing as the rice cooker was roughly re-assembled before they were let on their way with a small grunt and a hollow “enjoy your visit”.

“Oh we are here to stay,” laughed his mother, locking eyes with the customs man.

“Right,” he said dismissively, signaling to the next in line.

She shooed Zhen forwards and they hurriedly made their way out of the airport, past the smiling posters of blonde families having beach picnics. He carried a stuffed black bear which was almost as big as he was, and as he held it, paw to hand, scurrying after his mother he tried to imagine himself and Bear in the place of the posed couple, trapped forever clinking wine glasses against an ocean backdrop.

On his first day at the new school his shoes were wrong. Lined up outside the classroom, Zhen’s sneakers stood out immediately against the sea of white. “Too colorful” said the note sent home from his teachers. “And uniform policy prefers laces over Velcro.” At roll call they’d gingerly announced his last name, getting confused by the unfamiliar order and mixture of letters.

“John,” he corrected, giving the name he’d picked from the small list his parents had come up with. It was in this extra time that his teacher noticed the shoes.

“Right,” she said dubiously.

His parents debated whether or not it was worth buying him a second pair, and decided not to. It was impractical.

“He’ll grow out of them in six months,” his father said. Zhen split in two again, and his new self kicked out at the offending sneakers.

“There’s no call for that,” his father said. “And what has your mother told you about this double act you keep pulling?” Zhen, sitting on the couch, raised his palms apologetically. His other, silent self scowled and disappeared again. His parents switched on the news and Zhen sat quietly, poring over the small comic book, trying to memorize the story of Monga and his own adjustment to their shared adopted home.

He’d already read it cover to cover, but kept coming back to the same three pages, the same face. Monga didn’t look like anyone from home, but he didn’t look like any of the people from their new street either. Zhen was enthralled. His parents wouldn’t let him take the comic to school—how will you learn if you just read the same thing over and over?—so he’d painstakingly drawn Monga’s face twice: one on the toes of each of his sneakers.

The other children were fascinated, but it became frustrating to try and explain who the character was. When he told them he was Australian, they scoffed, and when he said the man’s name was Monga, the other children squealed with laughter.

“MONG-a?” exclaimed his classmate Cody. “You drew a mong on your shoes?”

“Makes sense,” chimed in Lachy, pulling at the corner of his eyes. “Mongs drawing mongs.”

The nickname stuck.

Before school had started for the year, his parents received a booklist and some suggestions for what their child would need, day to day.

Sandshoes for P.E. and for going in the sandpit.

A fruit box for recess.

Something for Show ’n Tell.

They were an English-speaking household though Zhen and his mother were bilingual. Ten years too early for the internet and yet to make friends on their street, his father tried turning to the surprisingly unhelpful dictionary.

At recess Zhen opened his lunchbox full of carefully sliced peaches, banana and canned longan while the other children plunged straws into tetrapacks, slurping aggressively, speedily—racing.

“What’s that, Mong?” demanded Cody.

“My fruitbox?” replied Zhen, after a pause.

The hoots of laughter and streams of mocking gibberish followed him as he trudged towards the empty corner of the sandpit and flopped down, alone.

Mou mo! Wu zhou lat tat! Don’t touch it! It’s dirty! cried his mother at the back of his mind.

The ghost of her advice was right; the sand was probably teeming with germs, but he gingerly started digging one foot in, then the other, and soon was grabbing fistfuls and heaping them on top of his shoes. Half sunk in, the color and Monga’s face soon got buried by the most gentle of avalanches.

In the comic, Monga was just one of many going about his life against the background that Zhen had been told was the Real Australia. There were sparkling oceans, there were giant fields—and there were stretches of sand, the soft yellows and oranges making a false sea more expansive than anything he’d ever witnessed. Missing were the tall towers of home, the streets packed with people. Every Saturday morning he could remember, Ah Poh would come collect him and they’d navigate the market together. His grandmother was ruthless in her bargaining, rapidly firing off the list of what she wanted to buy along with the price she expected to pay—their shared monosyllabic language making conversation sound like rapid linguistic gunfire.

Their new home was slower; people savored sounds like John savored the lychees Ah Poh would unshell and pop in his mouth to keep him from complaining when their trips went for just a little too long. The shops here were different; clean, quiet. There were no crates leaking melted ice and fish scales onto a slippery floor. People didn’t talk, they just walked up and down in straight lines, stacking plastic and cardboard on top of each other in their trolleys.

Monga disappeared into the sand completely and the bell rang. Zhen felt himself split in two again, but this time there was no one to tell him off.

The New One stood up and followed his classmates into the schoolroom. Zhen stayed in the sand, and contemplated his shoes.

Over the following weeks Zhen was sometimes singular and sometimes plural—something which frustrated his parents and teachers alike. His father grumbled as he was forced, yet again, to inflate their blow-up mattress to accommodate “this silliness”. The new one merely grinned and played with his Tazos. Zhen ignored him. Another firmly polite letter had come home with him after the teachers finally noticed the drawings, and he was now tracing out Monga again, this time on the soles of his new, stark-white sneakers so no one would see.

He sat, or sometimes they’d sit, every Wednesday as his class rotated through their turns for show and tell. There were pinecones and older brothers’ trophies, VHS tapes of Disney cartoons, or ticket stubs from that weekend’s football. When Zhen raised his hand to ask why the ball a classmate had brought in was long instead of round, The New One flushed and shuffled further away.

When his week came, Zhen didn’t even need to think about it. He carefully packed the comic between two exercise books so it wouldn’t bend in his bag, and arriving at the classroom, slipped his backpack in the usual spot: above his nametag which the teacher had cheerfully decorated with a wombat sticker, between Hannah (emu) and Lachy (bilby).

Zhen was more excited than he had been all year; he was still “Mong” to most of his classmates, who seemed to have forgotten where they’d gotten the name to begin with. He’d kept quiet about the secret drawings that were slowly wearing away as he trudged from class to class, and from running around in the occasional game of chasey he would join in on—when asked.

“I brought my comic,” he told his table, sitting down before roll call. “It’s in my bag. You can all see it after lunch.” Cody, who sat opposite, looked at him. “Why? We won’t be able to read it.” Zhen stared briefly at Cody, before muscle memory brought his gaze back down to the desk—but he could still see the boy pulling up at the corners of his own eyes, making gibberish noises as the rest of the table giggled. He felt the split happen again, and The New One joined in, a beat after the others. Zhen stayed quiet, eyes fixed on the table, grinding his left shoe into the linoleum.

The other children were mostly disinterested in Zhen. He didn’t impress them at sport, and wasn’t the best at any of the other things that seemed important: drawing the straightest lines or having the most stickers on the book chart. He knew the alphabet but had sung different songs at his kindergarten back home, so didn’t know as many lyrics to the songs they’d sing each morning. On the occasions they did pay attention, it was usually to point out something he was doing wrong: tying laces with one loop instead of bunny ears; pronouncing words differently; not knowing the difference between dress and skirt.

At lunchtime Zhen retreated to his usual patch of grass. He’d just plunged the spoon into his thermos when two girls from his table ran up, halfway between upset and laughing. “Cody’s reading your comic,” one of them said, with a giggle at the end. “Thought you should know.” They retreated, Zhen’s eyes following them, then overtaking, looking over at the backpack shelf where he could see Cody and some friends crouched over something.

They’d gone by the time Zhen got to his bag, which was unzipped. The comic was shoved roughly in at the top, no longer protected by the exercise books. Every page was crumpled, some ripped in half. The New One walked into the classroom and sat alone at his desk, slowly running his fingers over the damaged pages. Zhen stayed at his bag, quietly looking down at his ruined book, before clenching his fists and moving in the direction of Cody.

Zhen remained plural.

It was ok at first. When it became apparent that the split was permanent, his father begrudgingly bought a second bed. To avoid confusion the family decided to call The New One John. John and Zhen started out quite alike, doing the same after-hours activities and speaking the language that no one else understood when they wanted to discuss things in secret during class. The line down the middle of their room began to appear slowly; Zhen’s side filling up with certificates proclaiming his aptitude for maths and science, John’s with sporting trophies and CDs.

“You boys are being a bit literal,” scolded their father as Zhen quietly ate fish with his parents while John sat in the other room, fuming that he wasn’t allowed to go to the sleepover that clashed with the festival no one else was celebrating.

They sat, side by side, in the middle of the night, in the house where they’d lived for almost ten years, eyes fixed on the television—watching the two towers fall after a frantic call from Ah Poh. Their mother came home from work the next day and quietly recounted how a colleague had asked her if she’d “heard the news”.

“Yes. We watched while it happened,” she’d replied.

“Isn’t it awful,” said the woman. “But your lot’s ok.”

Zhen’s face tightened, while next to him, John seemed not to have heard, too engrossed in the Paul Jennings book he’d gotten out from the library.

Once a month, their mother would call Ah Poh. After discussing their health complaints and listing the meals they’d eaten that day, Ah Poh would scold her daughter for letting Zhen split into two separate people, blaming both diet and the fact that she wasn’t at home enough. Then the phone would be handed to the boys to answer questions about how school was going; if they were eating enough; when they would be coming to visit. At the beginning John and Zhen would take turns answering. Eventually, though, it got to the point where John would make excuses; homework, tiredness, anything, to avoid talking on the phone, and Zhen and Ah Poh would be left alone, rattling off friendly fire.

Over time, the phone calls got fewer and further between. Even so, it took Zhen a surprisingly long time to realize that people had stopped seeing him altogether; it took him even longer to realize that it was John who had done this to him. He came home from school one day to see that his bed had been packed up and put in the garage. As he turned to go back in the house, his hand passed right through the doorknob.

John refused to give him an explanation. He screamed and shouted and begged, but his corporeal self pretended not to hear. Zhen sunk to the ground, and found himself dragged along in John’s wake, an invisible wall forbidding him to get more than 10 meters away.

“Uggh, shut up Mong,” was the most he got out of John in six months of solitude. He couldn’t remember what the original Monga looked like; the crumpled book was still squeezed in on his shelf, but you can’t turn pages with faded hands.

It took a few years, but Zhen got used to the silence. He lay dormant, watching himself reply to his mother’s home-tongue questions in English, watching himself refuse to take leftovers to school anymore.

He watched as the calligraphy set from Ah Poh got dusty, got moved behind the trophies and eventually found a home at the back of a cupboard, the wax seal on the ink never breaking, as the liquid slowly dehydrated, turning to residue; unusable.

He filled the long lonely stretches by drawing invisible pictures; his bedroom became the market as he traced his finger along the wall, creating crates and cages and characters who existed even less than he did, disappearing centimeter by centimeter in his wake. The times he felt seen were few, and he didn’t know if they were just the product of a desperate hope.

In their monthly phone call Ah Poh congratulated John’s mother on finally getting him past his phase, though, when the phone was handed to John, her disappointment at hearing dui mm zhi, mm ming bak more than anything else was readily apparent.

“Put me on the phone,” begged Zhen. “I can help”.

Zhoi gein. Goodbye. See you again. John hung up the phone.

It was university holidays and Zhen watched as his friends who’d never met him sat around a table, growing hazier with each round of the drinking game they were yet to grow tired of. A circle of cards surrounded a jug filled with a mixture of drinks and he saw himself pull an ace.

“RULE!” the group shrieked as one. But they were stumped; awash with power and dulled by alcohol, they were at a loss as to how to wield it. There was silence.

A boy with slightly darker skin than the rest stole a sideways glance at John as he sat, running his index finger along the edge of the card, waiting.

“I know,” he said with a grin. “We all have to speak in our first language. Or drink.”

Zhen found himself sitting in John’s place, the card now in his hand. People were looking at him. He burbled out a sentence in his long silent voice, perfectly pronounced. His friends laughed, and continued drawing cards. Zhen smiled, and behind him, in the corner, John was furious. When the final king was pulled, ending the game, the rumble switched them back and both sat in sullen silence: one filled with anger, the other hollowed out.

Ah Poh’s visit came at the worst possible time—in that period between exams finishing and getting results back. John was nervous, worried about failure in a year where the absence of school’s structure had exposed his laziness. “Vi-sit,” he’d intoned during their phonecall.

“Fisit,” she’d shot back. “Fisit?” The language they’d once shared had no call for the letter V.

Hou loi mei gein.

John sat alongside himself in the back of the car, watching Zhen’s knee bounce up and down as he gazed out the window. Their father found a park close to the entrance and they all clambered out. They saw the poster at the same time. Out of the corner of his eye, John could see Zhen looking down at the memory of colorful shoes, long since thrown away, then back up again, comparing. He blinked, turning away from Zhen, then stared straight ahead at the face he hadn’t seen since he’d wedged the crumpled comic in between two thick books, wincing as his bruised knuckles touched against the spines.

Dui mm ji he said, the words stiff, formal, and unheard.

I’m sorry he said, to himself, and to no one.

© Elizabeth Flux

ELIZABETH FLUX is an award-winning writer and editor whose fiction and nonfiction work has been widely published, including in Best Australian Stories, The Guardian, The Saturday Paper and The Big Issue. She was a judge for the 2019 Award for an Unpublished Manuscript for the Victorian Premier’s Literary Awards and is a past recipient of a Wheeler Centre Hot Desk Fellowship.

NICOLAUS GOGOR SETA DEWA is a freelance photographer and translator based in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. He has been translating since 2013, mostly movie subtitles. He also worked as a journalist with Kompas in 2017. Now, he mostly takes pictures, translates, and struggles to write a novel in his free time.

HANA MADNESS (born Hana Alfikih) is a Jakarta-based visual artist and mental health activist. In 2012 she talked in national media about her mental health struggles. Her art is her ultimate weapon to be seen, heard, and appreciated by her community. Most of her artworks are her interpretations of her mental conditions and turmoils. She has participated and exhibited her works in numerous festivals and exhibitions. She has also spoken in many seminars about mental health. In 2017 she was honored by Detik.com as one of the “Top 10 most promising young Indonesian artists” and in 2018 by Opini.id as one of the “90 young Indonesians with inspiring works and ideas”.